This is the first in a series of regular articles exploring the world of our fantastic marine fishes. Let’s start with a look at the amazing hammerhead sharks.

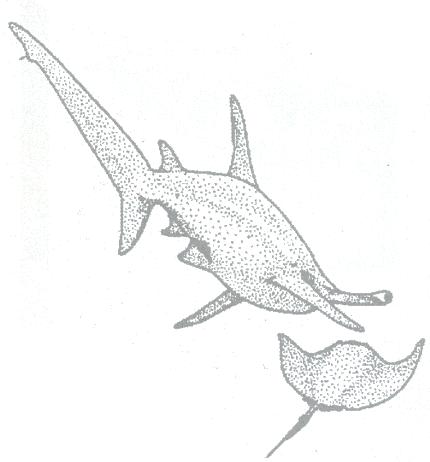

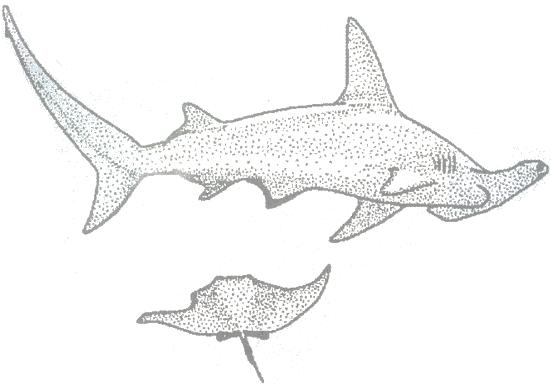

The hammerhead shark family Sphyrnidae comprises 8 species of sharks characterized by their distinctive flattened and broadly expanded head. Within the family there is a gradation from the slightly expanded head of the bonnethead shark, Sphyrna tiburo to the extreme lateral expansions of the winghead shark, Eusphyra blochii. One’s first impression of a hammerhead evokes thought’s such as “Wow, these sharks are really weird!.” and “I wonder what uses this strangely modified head can have?”

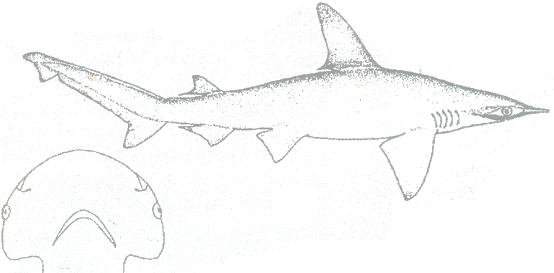

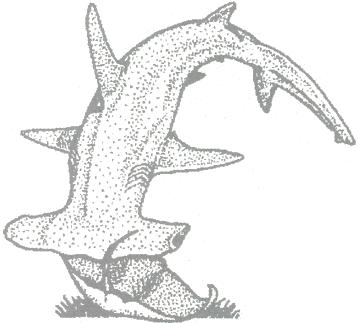

Bonnethead shark and underside of head.

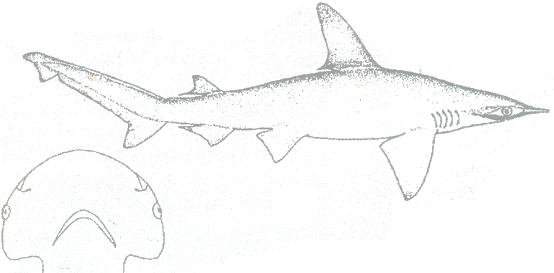

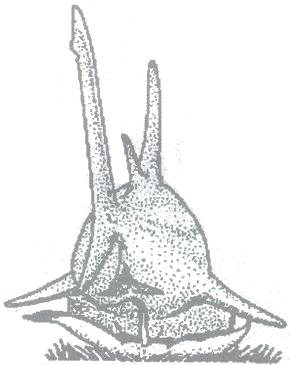

Winghead shark and underside of head.

To understand the functional advantage(s) of various anatomical adaptations, ichthyologists use comparative anatomical research, observations of the behaviour of live fishes, and experiments designed to test hypotheses about the function(s) of the structure in question. All of these methods of investigation have been used to shed some light on the advantages of the hammerhead’s expanded head.

FEEDING BEHAVIOUR

One of the favourite foods of the two largest species of hammerheads are stingrays, and the venomous tail spine of stingrays is obviously no deterrent to these formidable predators. Several large hammerheads have been caught with numerous stingray spines embedded in and around their mouths. A great hammerhead has been reported with as many as 96 stingray spines stuck in and around its mouth! Thanks to the fortunate observations of a hammerhead attacking a stingray by three shark researchers, we have a remarkable description of the use of the shark’s head in prey handling. The following edited description of predation by a great hammerhead attacking a southern stingray is taken from the paper by Wesley Strong, Jr, Franklin Snelson, Jr and Samuel Gruber published in the journal Copeia, 1990, No. 3.

“During an ongoing study of stingray biology, we observed the pursuit, attack and consumption of a southern stingray (Dasyatis americana) by a great hammerhead shark, (Sphyrna mokarran). A large stingray, moving at what appeared to be maximum speed, swam beneath [the observer] and directly toward the wreck [a sunken barge used as a refuge by the local stingrays], which was well beyond visible range. Seconds later, a great hammerhead approached from the same direction as the ray. This shark was a female, estimated at 3 m TL [total length] from photographs ... It swam near the two observers on the surface, then dropped rapidly to the bottom in pursuit of the stingray. The shark accelerated and closed the distance between it and the fleeing ray in about 8 seconds. Upon reaching the ray, the shark swung its head downwards in a hammer-like blow onto the back of the ray, sending the ray down to the bottom with great force.

The ray struck the grassy substrate and rebounded as the shark braked with lowered pectoral fins.

The hammerhead immediately delivered a second blow. Unlike the previous hit, however, the shark maintained contact between the front of its head and the back of the ray, pushing the stingray to the bottom.

The shark then pivoted on top of the ray and closed its mouth over the front margin of the ray’s left pectoral fin. With several lateral head shakes, the shark cleanly bit off a crescent-shaped chunk of flesh from the ray.

The shark then circled widely; and the ray resumed flight, exhibiting what appeared to be a highly motivated attempt to reach the [safety of the] wreck.

Although moving at a much reduced speed, the wounded ray maintained a direct bearing for the wreck, now an estimated 50 m away. Within 10 m of the wreck, the hammerhead overtook the ray and forced it to the sand bottom. Again the shark used its head to restrain the stingray as it pivoted and took a second, similar bite, this time from the right front pectoral margin.

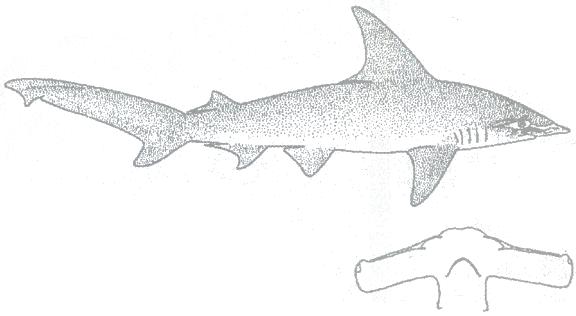

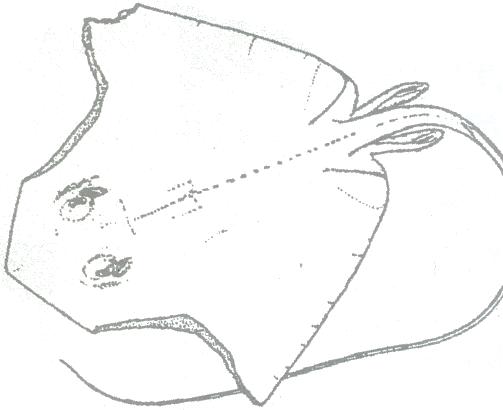

Stingray after two bites from the hammerhead

Although actively respiring [judged by the opening and closing of the spiracles] and curling its fin margins, the ray was incapacitated and did not move while the shark swam diminishing circles around it for 24 minutes. The presence of two swimmers on the surface and a SCUBA diver on the bottom about 6 m from the ray may have inhibited the shark’s immediate return to the prey. Other fishes (a remora, Echeneis naucrates; a grey snapper, Lutjanus griseus, a yellowtail snapper, Ocyurus chrysurus; and a bar jack, Caranx ruber) actively scavenged small pieces from the ray’s open wounds and showed no fright response to the circling shark during the 24 minutes before the shark resumed feeding. The moribund ray did not resist when the shark grabbed it by the head and swam directly away from the wreck.

The shark swam about 25 m, then resumed

consumption of the ray. Sawing and tearing sounds, produced by rhythmic

lateral head-shakes were clearly audible. This action cut quickly

through the front of the ray’s head, and the remaining carcass fell to

the bottom. Circling rapidly, the hammerhead returned and recovered

its prey. The shark repeated this feeding act (i.e., bite/drop/pick

up) four times as it continued on a relatively straight course away from

the wreck. Before the hammerhead returned for the final pick up,

a blacktip shark about 1.8 m scavenged off a small portion of the ray’s

midsection, then circled back as if to take a second bite. The hammerhead

sped in, mouth partially agape, and the blacktip veered away. The

hammerhead then engulfed the remaining carcass head first and swam away

with the ray’s tail hanging from its mouth.”

The function of the hammerhead sharks’

widely-expanded head in prey capture and handling is obvious from the description

of this predation event. Three times during the attack, the shark

used vertical blows of its head to strike the ray. The delivery of

each blow was smooth in that the final thrust was continuous with the swimming

movements, yet was faster and resulted in forceful impact.

Anatomical and physiological research

by Kazuhiro Nakaya in Japan has demonstrated that hammerheads have

specially developed muscles on the underside of their head that can depress

the head to a considerable degree, whereas other carcharhiniform sharks

can only elevate their head. The ability to depress as well as elevate

the head will have a significant hydrodynamic effect and provide greater

manoeuverability for the hammerhead.

The greatly expanded underside of

the hammerhead shark’s head will also increase the effectiveness of its

electro-receptive sense by spreading the sensory organs (ampullae of Lorenzini)

over a greater area.

In view of these significant advantages, it is apparent that the hammerhead’s flattened and laterally expanded head is of benefit in several respects to this unusual shark.