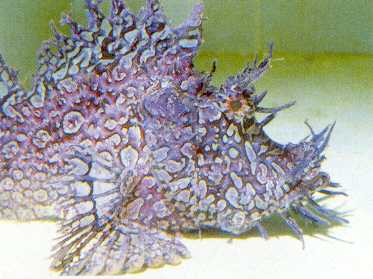

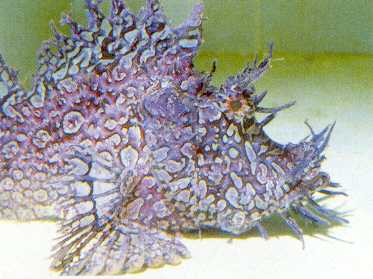

Rhinopias frondosa, photo: Peter van Niekerk.

Two Oceans: A Guide to the

Marine Life of Southern Africa.

By George Branch, Charles

Griffiths, Margo Branch, and Lynnath Beckley.

David Philip Publishers

Ltd, Cape Town. 1994. 360 pages.

ISBN 0-86486-250-4.

Reviewed by P.C. Heemstra.

This excellent guide to the marine life of southern Africa is well known to most people interested in our rich marine fauna and flora. It is simply the best general guide to the common plants and inshore animals of our area. It covers the full gamut of shallow-water invertebrate animals from sponges, cnidarians (jellyfishes, sea anemones, corals, sea fans etc.), flat worms to ascidians (sea squirts). The marine vertebrates (hagfish, sharks, rays, chimaeras, bony fishes, reptiles, birds and mammals) occupy less than a third of the book.

Most of the beautiful colour photographs that illustrate the species were taken underwater and show the animals in their natural habitats. On the page facing the photographs is a brief text giving diagnostic characters to identify the species, normal adult size (for invertebrates) or maximum size (for fishes), and notes on biology (for most species). A map showing the distribution in the southern African region accompanies the text for each full species account. Related, less common, species are illustrated with a photo or drawings, and the text for these species is just a sentence or two, with brief notes on diagnostic features and (for some species) habitat and/or distribution.

An annoying feature of the layout is the position of the page numbers, located near the inner margin of the pages. This makes it difficult to quickly locate a particular page.

The fish section comprises about 255 species, not counting the brief mention of “related species”. Most of the fishes are easily identified from the excellent photos, the vast majority of which were supplied by Dennis King.

The rationale for the grouping of fish species seems to be that superficially similar species should be placed together for ease of identification. The numbering system is apparently an ad hoc method of coordinating text and names with the photos.

Unfortunately, the supposed diagnostic features that are given in the text for many species are too vague or variable to be effective in distinguishing closely related species. For example, the identifying characters of the dusky shark, Carcharhinus obscurus, given as “Dusky grey; snout broad and rounded. Upper teeth triangular. Characteristic mid-back ridge; first dorsal fin small, second dorsal low.” This diagnosis would also fit the bignose shark, Carcharhinus altimus, or the Zambezil shark, C. leucas (aka the ‘bull shark’).

* * *

Herewith some corrections and comments to aid folks who want to improve their identifications and sort out changes in fish names.

The blue stingray (page 216) was also previously known (in Smiths’ Sea Fishes) as Dasyatis pastinaca (Linnaeus, 1758), but Leonard Compagno and Paul Cowley determined that Linnaeus’ species (which lives in the Mediterranean and northeastern Atlantic Ocean) is different from the blue stingray in our area. Hence, we now use the name (correctly given in the Two Oceans book) Dasyatis chrysonota, which was bestowed on our species by Andrew Smith, the first South African ichthyologist, in 1828.

The photo labelled “Rhinobatos annulatus” is problematic; the colour pattern is different from both the Cape and Natal forms of annulatus, and the snout seems too blunt for annulatus. Another possibility is Rhinobatos blochi Müller & Henle, 1841, the juveniles of which have a few small pale spots on the disc and tail; but blochi is known only from Cape Point to Walvis Bay.

The sawfish labelled “Pristis pectinata” is Pristis zijsron Bleeker 1851. Thirty years ago sawfishes may have been common in Lake St Lucia and Richards Bay, but for the past 10 years, sawfishes have been rare in our area.

The zebra moray (page 218) has recently been shifted to the genus Gymnomuraena, so the correct name is now Gymnomuraena zebra.

We have two species of popeyed scorpionfish (Genus Rhinopias) in our area. The one shown on Plate 106 is Rhinopias eschmeyeri Condé, 1977, as indicated by the unique round, fleshy flap above each eye. Rhinopias frondosa has elongate branched tentacles above the eyes, fleshy tentacles all over the head, body and fins, and a colour pattern of many spots and streaks.

Rhinopias frondosa,

photo: Peter van Niekerk.

The colour characters given for Pterois radiata and P. russellii are the wrong way round; it is radiata (not russellii) that has 5 or 6 broad dark bars on the body, and 2 or 3 horizontal white stripes on the caudal peduncle.

Radial firefish, Pterois

radiata.

The snout of the pipefish identified as Syngnathus acus (page 228) appears much too short for acus (perhaps the snout was pointing obliquely away from the camera when this photo was shot.

It is rather misleading to describe the trumpetfish as “brownish”. In fact the colour of this species is quite variable; it can be brown, grey, greenish or bright yellow, but always shows the two black spots at the upper and lower edges of the caudal fin. The darker varieties often show pale vertical bars when they are actively hunting.

Pomadasys olivaceum (page 234) is called a piggy in the Eastern Cape Province, but in KwaZulu-Natal it is known as a ‘pinky’ -- another example of why we should use scientific names when we are talking about fishes.

The fish misidentified as the Russell’s snapper, Lutjanus russellii (page 237) is actually the onespot snapper, Lutjanus monostigma (Cuvier, 1828). The black spot on the flanks of L. russellii is larger and mostly above the lateral line; and adult russellii in the Indian Ocean usually show 7 or 8 narrow, golden-brown stripes running longitudinally on the body from the head towards the dorsal and caudal fins.

Lutjanus russellii

The distribution of the Natal knifejaw, Oplegnathus robinsoni, (page 248) extends south to at least Aliwal Shoal.

The kob shown in the photo on page 251 are the squaretail kob, Argyrosomus thorpei Smith, 1977, known only from Port Elizabeth to the Tugela River. Thanks to the recent research of Dr Marc Griffiths, the confusion in the taxonomy of our kob species has been resolved. The species that is properly called A. hololepidotus is known only from Madagascar. Our common, large, inshore species of kob, now known as the ‘dusky kob’, Argyrosomus japonicus (Temminck & Schlegel, 1843), occurs from False Bay to the northern Indian Ocean and over to Japan and Australia. The dusky kob attains a length of at least 181 cm and a weight of at least 75 kg. It is common in estuaries, and the fresh fish has a ‘brassy’ odour.

The very similar ‘silver kob’, Argyrosomus inodorus Griffiths and Heemstra, 1995 is a smaller species, maximum size about 90 cm. It differs from A. japonicus in several features, the most obvious being a longer, more slender caudal peduncle (peduncle depth 58–74% of peduncle length; versus 70– 92% in A. japonicus) and the fresh fish has no odour. The silver kob occurs from Namibia to at least the Kei River in the Eastern Cape Province; in the region from the Kei River to Cape Agulhas, the silver kob is usually caught at depths of 10 to 100 metres and rarely enters estuaries or the surf zone.

Batfishes (Genus Platax) are often confused, and the photo (page 253) identified as ‘Platax orbicularis” is actually the longfin batfish, P. teira (Forsskål, 1775). P. orbicularis lacks the dark streak in front of the anal-fin origin.

The old woman angelfish was previously (in Smiths’ Sea Fishes) known as Pomacanthus striatus (Rüppell, 1836), but that name was shown by Jack Randall to be based on a juvenile of Pomacanthus maculosus (Forsskål, 1775), which occurs in the Red Sea and northern Indian Ocean. Consequently, the Two Oceans book correctly used Pomacanthus rhomboides (Gilchrist & Thompson, 1908) as the valid name for the old woman, which is known only from southern Africa. Adults are found from southern KwaZulu-Natal to Maputo; juveniles are occasionally caught as far south as Knysna.

The limespot (or ‘teardrop’) butterflyfish (page 256) of the Indian Ocean is now called Chaetodon interruptus Ahl, 1923. Chaetodon unimaculatus is a similar species restricted to the Pacific Ocean.

The coachman, Heniochus acuminatus and the schooling coachman, Heniochus diphreutes are very similar and often confused (see Smiths’ Sea Fishes, plate 77 where the painting of H. diphreutes was wrongly labelled as ‘Heniochus acuminatus’). See diagram on back page of The Fish-Watcher No. 2 for characters to differentiate these two species. The Two Oceans photo (page 257) that is labelled H. acuminatus appears to be H. diphreutes.

The shoal of kingfish identified as yellowspotted kingfish, Carangoides fulvoguttatus in the photo on page 259 are blue kingfish, Carangoides ferdau, the adults of which often show 5-6 dusky bands on the body (as in the photo).

Carangoides fulvoguttatus

Photograph 122.4, misidentified as Caranx ignobilis, is an excellent photo of the brassy kingfish, Caranx papuensis. Characteristic colour features of the brassy kingfish are the upper half of head and body with small black spots, becoming more numerous with age, the upper caudal-fin lobe uniformly dark, and the lower lobe dusky to yellow with a narrow white rear margin.

Caranx ignobilis is mainly silvery grey to black above, usually paler below; fins usually uniformly pigmented grey to black. It attains a fork length of 165 cm and weight of at least 63 kg.

Giant kingfish, Caranx

ignobilis

The blacktip kingfish is now Caranx heberi Bennet, 1830, an older name for the species named Caranx sem by Cuvier, in 1833.

Large adults of the golden kingfish, Gnathanodon speciosus lose the golden yellow colour and black bars of the juveniles and are mainly silvery, with irregular black blotches and spots. The young are often seen exhibiting ‘piloting’ behaviour by swimming in front of sharks and other large fishes.

The eastern little tuna, Euthynnus affinis, (page 262) is not so little; it attains a weight of at least 16 kg.

The king mackerel, Scomberomorus commerson (aka ‘narrowbarred mackerel’) attains at least 220 cm fork length and 46 kg. This species is wrongly called ‘barracouta’, ‘barracouda’, ‘cuda’ or ‘couta’ by some anglers in KwaZulu-Natal; the true barracudas are in the Family Sphyraenidae.

The blue humphead parrotfish (page 270) has recently been shifted to another genus, so the scientific name changes to Chlorurus cyanescens.

The “mudhopper” shown on page 279 is Periophthalmus argentilineatus (Valenciennes, 1837).

So much for the fishy technicalities. The Two Oceans book is not only indispensable as a guide for identification of the common marine invertebrate animals, but it is also useful for identifying many of the common marine fishes one encounters in the near-shore environment.